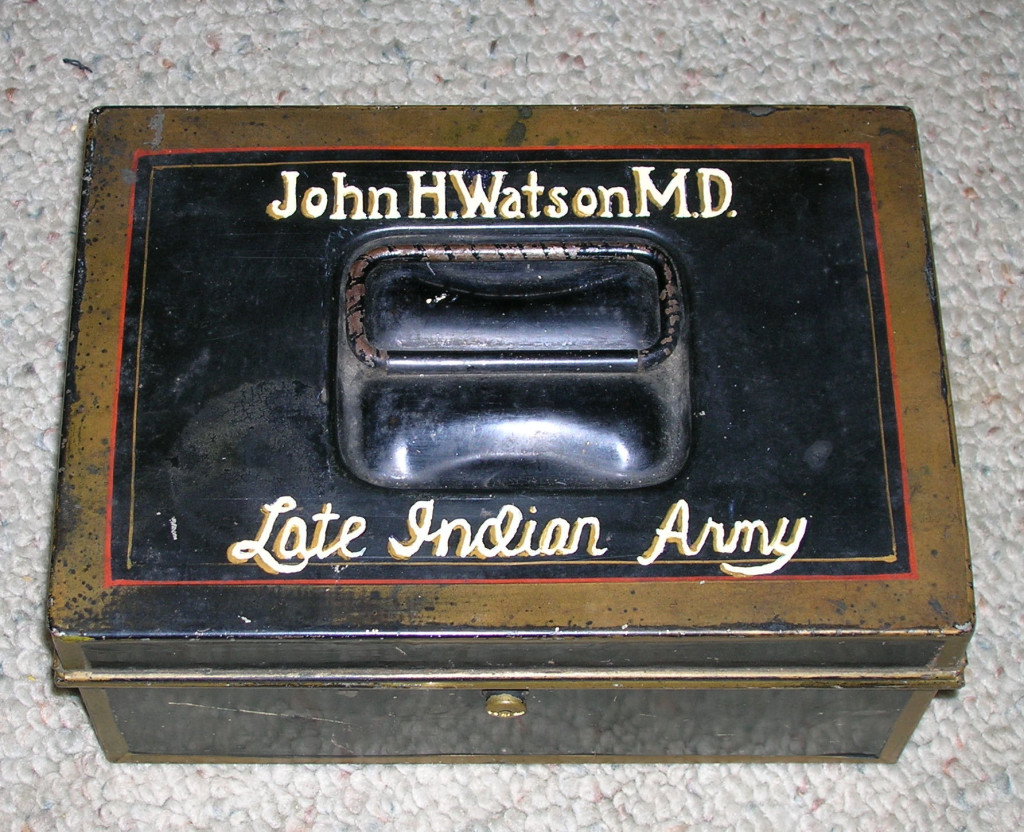

In the final collection of stories called The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes is The Problem of Thor Bridge. At the start of Watson’s recounting of this case, he mentions a travel-worn and battered tin dispatch-box inscribed with his name “John H. Watson, M.D., Late Indian Army” painted on the lid. Despite many claims by authors purporting to have found one of the many Sherlock Holmes cases that Watson chose not to make public in this tin box, it has never been found.

To ascertain its true whereabouts, consider the following. Watson says that the dispatch-box is somewhere in the vaults of the bank of Cox & Co., at Charing Cross.

The founding of Cox & Co dates to 1758. Lord Ligonier, Colonel of the 1st Foot Guards, appointed his secretary, Richard Cox, as regimental agent. Cox was responsible for the payment of officers and men, and the provision of clothing and the marketing of officer commissions. He operated the business with the help of two clerks at his house in Albemarle Street, London until his death in 1803.

The firm continued and went from strength to strength. By 1815, it had become agent to the entire Household Brigade, most of the cavalry and infantry regiments, the Royal Artillery, and what was later known as the Royal Army Service Corps. The company had moved to Craig’s Court in Whitehall, in 1765. But by 1888, Craig’s Court was no longer large enough to accommodate the staff, which had increased to 150. So, the firm moved to bigger premises at 16–18 Charing Cross. This is where Watson had deposited his dispatch-box.

Between 1905 and 1911, Cox & Co. expanded further, setting up branches in India, Alexandria, Egypt, and Burma. The business expanded dramatically with the outbreak of the First World War. Its staff increased from 180 in 1914, to 4,500 in 1918. With a third of the original work force having joined up, the firm had to recruit women for the first time. The branch had around 250,000 men on its books. At the height of the conflict 50,000 cheques a day were cleared.

Cox & Co. took over the firm of Henry S. King in October 1922, and the bank was renamed Cox’s & King’s. Despite the merger with King’s, Cox & Co. was in serious trouble as it was unable to sustain the large expansion undertaken during the First World War. By 1923, the bank was recording losses of more than £1 million a year, against a capital and reserve of roughly the same amount. After receiving assurances from the Bank of England, Lloyds Bank was persuaded to step in and take over the firm.

Leslie Klinger, in his Annotated Sherlock Holmes Volume 2, mentions that at 48–49 The Strand is the Charing Cross branch of Lloyds Trustee Savings Bank, and a sign above the entrance declares “Cox & Co.” and that for this reason this location has been traditionally identified this location as the home of Watson’s dispatch-box.

This assumes that, at the takeover of Cox & Co, Lloyds were diligent enough to move all the assets of Cox & Co to their new location. This also assumes that the records of Cox & Co mentioned Watson’s dispatch-box and that Lloyds were thorough in moving all such items from 16–18 Charing Cross to 48–49 The Strand. As the dispatch-box has not come to light since the takeover, the only logical conclusion is that it was not moved from the vaults at Charing Cross or, if it was moved, its identity was lost and therefore the value of its contents. Also, at the time of the takeover, Watson was in no fit state to take possession of his dispatch-box even if it had been asked of him.

As well as the large number of papers relating to Sherlock Holmes cases, the dispatch-box is thought to contain the only surviving manuscripts of the three volumes of the Reminiscences of John H. Watson, M. D., late of the Army Medical Department. A Study In Scarlet, the first story that Watson published, is from the second of these three volumes of the doctor’s writings.

Leave a Reply